Amid the football and Hollywood award shows this weekend, I had the opportunity to hear a lecture by Andy Bunn, a scientist at Huxley College of the Environment at Western Washington University, who described science fiction turned science fact: Pleistocene Park.

This is a real-life experiment by Russian ecologist Sergey Zimov to convert forested tundra in Siberia to a Pleistocene-like grassland to keep permafrost frozen. The restored landscape would help prevent a catastrophic loss of carbon to the atmosphere and runaway global warming.

Andy was a colleague when I taught environmental journalism at Huxley, and he visited my classes to talk about climate change and his research in Siberia. Since 2014 appears to be the warmest yet on historical record – and since another Jurassic Park movie is scheduled for 2015 – his talk in my town of Anacortes was timely.

Andy was a colleague when I taught environmental journalism at Huxley, and he visited my classes to talk about climate change and his research in Siberia. Since 2014 appears to be the warmest yet on historical record – and since another Jurassic Park movie is scheduled for 2015 – his talk in my town of Anacortes was timely.

Bunn has been traveling for a decade to a remote area of Siberia near Alaska called Chersky, researching how melting permafrost is pumping more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. For those who have played Risk, the nearest city – a four-hour flight away – is Yakutsk. Chersky is a former gulag area that now is almost complete wilderness, and its simplistic larch ecosystem is devoid even of most animals.

The American faculty and students who work there each summer have teamed with Zimov, a bearded eccentric out of Hollywood casting. The Americans want to know how quickly carbon is escaping from thawing earth, and the Russian wants to learn how to stop it.

Zimov is manipulating the environment in ways that would never be permitted in North America. He has fenced off tens of thousands of acres of taiga, or forest, knocked down the trees with a modified tank, and brought in browsing animals like arctic horses and musk ox to keep the trees out by browsing.

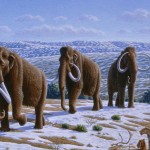

He is trying to replicate the grassy savanna that dominated Siberia in the Pleistocene, or the 1.8 million period most of us call the Ice Ages. The latest cold spell began to pause about 20,000 years ago. Human civilization has risen in the warm interim.

Unlike North America, Siberia was not covered in glaciers in the Ice Age. Instead there was grassy tundra from northern China to Europe, dominated by huge grazing animals such as the woolly mammoth. This ecosystem sucked carbon out of the atmosphere and locked it into icy permafrost soil.

Bunn explained that the grass growth of summer consumed carbon dioxide, and the bitter cold of winter prevented rot and release of the carbon. Instead, the dead grass – carbon – was frozen into the ground, never warming because the white snow cover reflected so much sunlight.

As the planet has warmed, larch trees have replaced the grass, and their dark mass absorbs more sun, accelerating permafrost melting. Result: more and more frozen carbon is released into the air and water. The potential, Bunn, said, is a “carbon bomb” of potential climate change. The carbon locked in permafrost dwarfs that already in the atmosphere, and could radically heat the earth.

Keep out the trees, Zimov reasons, and you slow or halt the melting and the release of carbon. Pleistocene Park is an experiment to prove or disprove that idea.

An even wilder idea is using DNA from frozen mammoths to recreate the species by implanting it in Asian elephants. That’s still science fiction, but fiction has had a habit recently of becoming eventual fact.

Even if Zimov is right, it’s hard to imagine converting enough taiga forest to make a real difference. Environmentalists would likely object, and it’s probably easier to clean up coal emissions. But it’s a fascinating step in trying to understand the mechanics of how land use affects climate.

Oh, and if woolly mammoths were helping store carbon, why did the latest Ice Age end? Because the earth’s orbit around the sun varies over tens and hundreds of thousands of years, Bunn said, producing cyclic changes. After the recent warm spell our orbit is due to make earth colder again, but greenhouse gases are swamping that trend and will likely send temperatures hotter the next couple centuries.

We’re racing to get a handle on this climate yo-yo and our own policies. Slowing global warming gives humankind more time to understand and adjust.